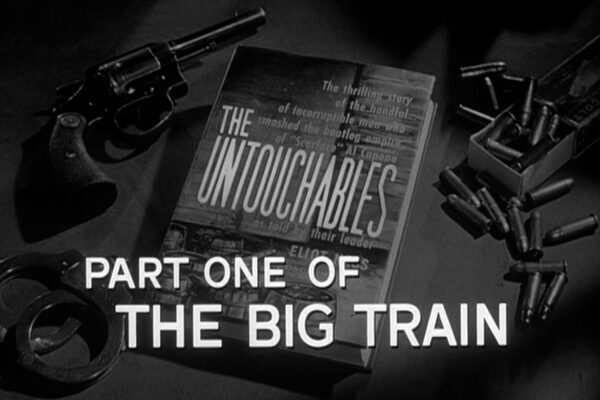

PART ONE OF THE BIG TRAIN

Airdate: January 5th, 1961

Written by William Spier

Directed by John Peyser

Produced by Josef Shaftel

Director of Photography Charles Straumer

Special Guest Star Neville Brand

Co-starring Bruce Gordon

Featuring Richard Carlyle, Gavin MacLeod, Lewis Charles, Frank London, Lalo Rios

“On October 17th, 1931, in a federal district courthouse, the trial of Scarface Al Capone, which had lasted eleven days, came to an end. The man responsible for the arrest and conviction of Capone was Eliot Ness. Ironically, the two men, opposing chiefs in a bitter warfare, had never met. And although Capone, as he was taken from the Chicago courtroom on November 24th, 1931, passed within a few yards of Ness, he did not recognize the leader of The Untouchables.”

As Al Capone (Neville Brand) boards a train bound for prison, an enthusiastic crowd bestows him with gifts and praise and an onlooker claims he’ll still be king in the Atlanta Penitentiary. Struck with the thought that Capone’s influence may hardly be diminished, Eliot Ness advocates for the construction of a special institution for unrepentant criminals – a remote prison facility called Alcatraz.

Capone handily enjoys the support of corrupt prison guard Ed Lafferty (Richard Carlyle) and quickly learns he’s to be transferred to Alcatraz by train. Before leaving Atlanta on probation, a disgraced railroad detective (Frank London), commits to helping the Capone mob plot to intercept the train on its route west to San Fransisco as Alcatraz nears completion.

Concerned that the gang is suddenly liquidating its assets for cash, Ness alerts prison officials who take steps to beef up security for the train. Capone manages to send his cohorts the last bit of crucial information needed to spring his release: the date and time of the train’s departure from Atlanta.

“At the precise minute of midnight of 5 AM on August 19th, exactly on schedule, The Big Train moved out of the Atlanta prison yard. At some western spot, at some time in the next 72 hours, the Capone mob planned, with violence and bloodshed, to free the most famous criminal in all American history. Eliot Ness and the Untouchables were tasked with preventing a national disaster which was scheduled for a place and an hour unknown to them.”

REVIEW

The Big Train is an outlandish scenario, but that’s what television is often about. This story stretches the Capone saga further with Neville Brand returning as mobster Mr. Big – and it has the special distinction of serving as a direct sequel to the original Desilu Playhouse drama.

Following the stellar two-part The Unhired Assassin in the First Season, screenwriter William Spier was tasked once again with mashing together historical fact and Untouchables fiction. The Big Train‘s biggest advantage comes in being able to take Capone’s name from the shadows where it usually lingered and thrusts the character himself into the center of a prison break/train heist film. Thankfully, Spier withholds the details of the heist and his scenes bring us in just before or right after its details have been exchanged, leaving us to experience the mystery from Ness’ perspective.

While The Unhired Assassin managed ambitious gravitas, The Big Train is a little disjointed. Part One sets up Ness as the primary driver behind the creation of Alcatraz prison as a means to reduce Capone’s stature and influence. From there, the hour is filled with petty prison guards, code words, heist planning, and happenstance meant to set up the more action-packed second installment whose broadcast was threatened by a growing contingent of detractors who were determined to ensure it would never see the light of day.

THE BIG TRAIN WRECK

Several serious problems for The Untouchables were not about to disappear. In fact, they would only intensify as the popularity of the series grew. As the Italians prepared a new volley of complaints, The Big Train steamed into town.

The first installment of The Big Train made Federal Prison Director Jim Bennett utterly furious. In a letter fired off to FCC Chairman Frederick W. Ford, Bennett complained that the story was a deliberate deception and that ABC should have announced it as such.

An excerpt of a story carried by UPI in The Alexandria Times-Tribune on January 13th, 1961.

What upset Bennett the most was the depiction of an Atlanta prison guard as corrupt. “To picture honorable and courageous officers as venal, and a public institution like the Atlanta Penitentiary as toadying to a character like Capone, is an unfortunate public disservice,” Bennett told New York Post writer Bob Williams, in a story published January 13, 1961.

The network, extremely proud of its hit series, politely brushed off the criticism despite Bennett’s warning that he would fight license renewals of ABC’s affiliates if they aired the second installment slated for Jan. 12.

Network vice president Omar F. Elder, Jr., send a telegram to Bennett indicating that one unflattering characterization of a prison guard should not be construed to be “representative of, or casting any general reflection upon the integrity of other members of that group.”

ABC was not about to cancel an episode of the series that was putting it on equal footing with pack leaders CBS and NBC, but when the phone rang in New York with a call from the man who claimed to have been the prison guard in charge of Capone’s cell block at Atlanta thirty years earlier, ABC lawyers went into vapor lock. The phones lit up at Desilu Gower with requests to discuss the matter with the research team. How could they have missed this one? Did they bother to check with Atlanta on this? Exactly how many more lawsuits would they like to entertain?

Part Two of The Big Train would air a week later, but with a hastily prepared disclaimer clumsily cut into the head end: “The events portrayed in this film are fictitious. The federal prison guards portrayed do not represent any actual persons living or dead. Nothing herein is intended to reflect unfavorably on the courageous and responsible prison guards who supervised Capone during his internment at Atlanta and during his transfer from Atlanta to Alcatraz.”

Like the Ma Barker story the first year, The Big Train was trouble waiting for an air date. Unlike the Barker case, it had generated a lot of bad press when the program’s popularity was at its zenith and raised the public’s level of consciousness to the fact that these stories were simply not true. For some viewers, it was an untidy and untimely return to the $64,000 Question even though Quinn Martin had more or less explained the program’s cavalier, but not unreasonable legerdemain in a TV Guide story six months earlier.

The problem was in the presentation. It was simply too official, too authentic in its documentary style to be fiction and viewers had great difficulty accepting it for what it was. A documentary was naively assumed to be history, plain and simple. It could take an honest, it’s-all-written-down-somewhere approach while leaning to the left or swerving to the right to serve the particular filmmaker’s interest, but it was simply a given that all of the facts were true, like so much evidence in a court of law. Why this was so remains one of the great mysteries of the universe.

Every means of communication ever devised has suffered from gross distortion of one sort or another, but each has enjoyed a brief moment of relative integrity in the eyes of the beholder before becoming tools of the devil. And each time, the masses are taken back anew when it is revealed that what had appeared to be real, was smoke, mirrors, and greasepaint. The audience, having bought tickets to the play, was stunned to find a performance being given.

Few realized it at the time, but The Untouchables had brought to television what would soon come to be known as the docudrama. The basic recipe for stirring fact and fiction into the theatrical pot to see what steamed forth had been done before, of course, but not since Orson Welles’ legendary War Of The Worlds, the 1939 radio play that caused a panic, had such a large following been snookered by what they thought was the news.

The Untouchables did for television what Winchell himself had done for journalism almost forty years earlier. It boiled a few salty facts with enough Tabasco to reach critical mass and exposed the medium as an instrument of boldly versatile, engagingly clever entertainment. But the end of the golden age of innocence was certainly at hand. Television’s tabloid era had begun.

For the remainder of the 1960-1961 season, each episode would bear a disclaimer in the closing seconds of the credits intended to mollify the program’s detractors:

“This series of programs is based upon the novel The Untouchables by Eliot Ness and Oscar Fraley although certain portions of this episode were fictionalized. “

It was the first time a television program had to confess to being a television program. From the beginning, a given episode’s writer shared billing with a line intended to reinforce the notion that the story was based upon the book. Misleading, yes, but perhaps a great deal more honest than stating unequivocally that certain portions of a particular episode had been fictionalized, when in fact, there was simply nothing in Ness’s book upon which to base virtually any episode that did not directly involve the pursuit of Capone. The Rusty Heller Story might have been the single exception to that, in that it was a splendidly fabricated sidebar to the essentially true Ness-Capone affair. The rest of the season is grand fantasy.

A later version of the disclaimer would be more accurate, but perceptive viewers, those already clever enough to figure out that they had been watching television all along, knew that this was storytelling, pure and simple. Tall tales, nothing more. Pull up a cracker barrel and set a spell.

For most viewers, The Untouchables was still well worth the hour spent even if it was fiction. Viewers had found an all-American hero and nothing could diminish the fact that he had indeed been a real lawman of remarkably unspoiled character. (Whereas Sgt. Joe Friday of Dragnet, as popular as he was, never drew breath, as they say.)

To be sure, there was a measure of universal disappointment that the series was very simply just a TV show, albeit a rather spectacular one. If the series had shed any viewers, it failed to show up in the Nielsens. One week after Part Two of The Big Train, they were back in similar numbers for David Goodman’s clever episode, The Masterpiece – one of the finest episodes of the entire series.

The ratings held.

QUOTES

CAPONE: Ness? You’re Ness? I never even saw the guy. Now ain’t that a laugh. A man gets a drop on Capone and Capone doesn’t even know what he looks like. Hey, this is the bull that finally put me away on the income tax wrap. Well, here I go, 11 years. I gotta do it, so I do it. I ain’t sore at anybody, nobody. Not even you, Ness.

NESS: That’s mighty big of you.

OBSERVATIONS

• The network would not repeat these two programs, but early syndicated prints would bear a disclaimer stating that the story was fiction and should not be considered as reflective on the character of prison guards in general, spliced rather crudely into the head end of both programs. Later, Desilu would cut it into a feature-length item for television and call it Alcatraz Express.

• The stock footage of Dearborn Station is not only 100% accurate, but the set design and displays have historically appropriate railroad names and trains.

HISTORICAL NOTES

As part of their extensive research, co-authors A. Brad Schwartz and Max Allan Collins recently uncovered that Eliot Ness was indeed on hand to see Al Capone to Dearborn Station. Their book, Scarface and the Untouchable: Al Capone, Eliot Ness and the Battle for Chicago is the definitive history of Eliot Ness, Al Capone, and the real-life Untouchables. It has our absolute highest recommendation.

Ness (at far left) and Capone (center) on May 3rd, 1932 at Dearborn Station. This and another photo featured in “Scarface and The Untouchable” are the only two images featuring Eliot Ness and Al Capone together. Courtesy Cleveland Public Library and the Chicago Tribune.