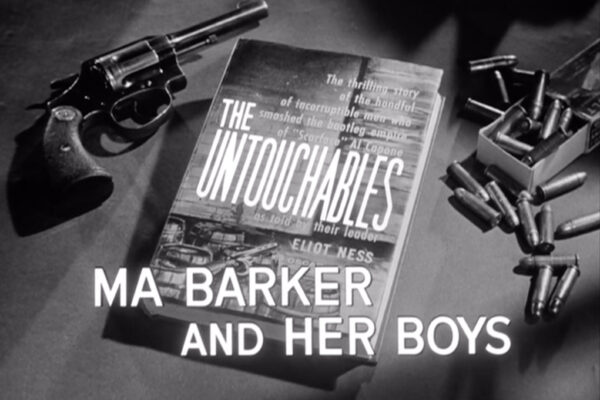

MA BARKER AND HER BOYS

Airdate: October 22, 1959

Written by Jerome Ross

Directed by Joe Parker

Produced by Norman Retchin

Director of Photography Charles Straumer

Special Guest Star Claire Trevor

Featuring Joe di Reda, Robert Ivers, Adam Williams, Peter Baldwin, Vaughn Taylor, Louise Fletcher

“One of the most astonishing episodes in the annals of American crime took place on January 16, 1935. It began at 7 a.m. on a warm, sunny Florida morning. In a combined operation, Eliot Ness and his agents joined with the state troopers and local police in a surprise visit near the town of Oklawaha, Florida. What followed made front-page headlines throughout the world.”

Kate Barker (Claire Trevor), is the church-going mother of four spirited boys with a penchant for petty larceny. After her youngest son is killed during a robbery, Pa Barker (Vaughn Taylor), abandons the family in frustration.

Unrestrained, Ma leads her progeny on an escalating crime spree throughout the Midwest. The publicity leads Pa Barker to Eliot Ness with vital inside information on the family and the Untouchables tracks the gang to Minnesota, where they narrowly escape capture. The trail runs cold until the eldest son, Doc (Peter Baldwin), breaks away with his new girlfriend, heads for Chicago and goes into hiding. There, he blunders into a trap that ultimately leads Ness into a fierce showdown with the Barkers in Florida.

“1:20 p.m., January 16, 1935. After more than six hours the battle was over. They found Ma Barker’s body in the parlor. The debris of the battle all around. They found Fred Barker nearby and in the sunroom was Lloyd Barker.The apron strings she had tied to them were finally untied and the case of Ma Barker and her boys was at an end.”

REVIEW

An interesting and relatively captivating hour despite it many serious flaws, Ma Barker And Her Boys runs rampant with some fairly dated acting. Claire Trevor’s portrayal of the infamous mother is often blatantly theatrical, but therein lies some of the program’s peculiar charm. Trevor interprets the whole thing to be simply another of her late 1930s films and that alone goes a long way toward giving the program the look and feel of a traditional Hollywood gangster saga.

“It’s just the four of us….against the whole world.”

Trevor, an actress since childhood with stage experience and many screen credits, appeared with Stack and John Wayne, a few years earlier in The High And The Mighty.

Difficult as it is to tell a story spanning four years in something less than an hour, much of the Barker career is told as a summary flashback papered over with screaming headlines and Winchell updates. It works, however, and leaves the remaining time for the big showdown in Florida, where special effects wizard A.D. Flowers perforates the Barker hideout with as many rounds as might be fired in a small foreign uprising. Stack recalls Joe di Reda, as Fred Barker, receiving a painful lesson in timing when a nearby prop, a grandfather clock, splintered from machine-gun fire, driving wooden shrapnel into his thigh.

Joe di Reda flinches as he retreats from the exploding prop.

Some difficult moments include the discovery of Arthur (Doc) Barker in Illinois, thanks to having listed the serial numbers of the ransom money netted in a Minneapolis kidnapping with all Chicago merchants. That is easier to accept perhaps, than the idea of a birthday cake mailed from Florida, arriving in the Windy City completely intact, frosting and all. There are several scenes absent of direction. Some of the characters flat out don’t quite know what to do with themselves. Additionally, the Winchell narrations, as written by Jerome Ross, are largely uninspired.

“Happy birthday, Doc.”

QUOTES

While viewers and reviewers alike loved the Barker story, some were offended, but not by the carnage. Ma Barker had told Eloise (Louise Fletcher) to “say goodbye to Doc and get the hell out.” The words “hell” and “damn” were as rare to television then as microchips.

MOTHER OF INVENTION

It was the trailer for Ma Barker And Her Boys, appearing at the end of The Empty Chair, that blew her cover. That one of the most celebrated of all FBI cases had made its way into a Treasury agent’s portfolio, was a major shock and surprise for senior bureau officials, some of whom doubtless sat watching the 90-second promo registering incredulity.

The next morning, October 16, the memos launched.

In one to Clyde Tolson, J. Edgar Hoover’s closest aide and famous for giving flight to virulent memos of his own, an annoyed official penned his displeasure: “It is bad enough to do something like this and worse to have the FBI in a supporting role.” He would later discover that the FBI had no role whatsoever written into the script. Tolson, in reply, allowed that “we must find a way to prevent such subterfuge…it is a fraud upon the public.”

The next day, another official expressed his desire to see the FBI release a statement exposing the Barker episode as patently false, setting the record straight and questioning the integrity of the whole series, “particularly when the public is raising a cry at this time against other networks for falseness.”

Tolson ordered an official protest sent to ABC. “I see no reason for pulling our punches.” The extremely image-conscious Hoover and his staff were dumbfounded that something like this could happen without their consultation – an occurance all the more aggregious given Hoover’s limited but contentious relationship with the real Eliot Ness. Undoubtedly, they would have taken an axe to the machinery before the show had a chance to find its way onto Kodak stock, but here it was, ready to air in a week. They had, after all, just finished buffing their homogenized legacy in Warner Brothers’ production of The FBI Story, starring James Stewart and Vera Miles. Not only that, but less than a year before, Hoover’s thought police had approved the script for Lepke, a Desilu Playhouse dramatization of New York’s infamous Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, one of the principals of Murder, Incorporated. It was reasonable for them to assume they had complete control of anything that so much as mentioned the bureau or its illustrious history on film.

While Arnaz considered himself among Hoover’s many influential friends, their relationship was uneven. The suspicious Hoover is said to have maintained a private intelligence file on Arnaz, numbering some 200 pages. Hardly the stuff of true friendship. Arnaz had the script forwarded on the basis of what he assumed to be their mutual relationship and because Hoover had been personally involved in Lepke’s surrender in 1942. The bureau, of course, went through it with an abacus. The official analysis of Lepke noted that of the script’s 87 pages, Hoover was mentioned “favorably and respectfully” on 14. J. Edgar anointed it, Lepke aired and that was the end of it. Then came Ma Barker.

In a letter to Hoover, Arnaz apologized, calling the Barker episode a “terrible goof” and immediately peppered Quinn Martin with instructions to abandon plans to write Ness into a virtual season’s worth of material involving John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, Baby Face Nelson and a litany of other world-class criminals of the period.

It was an early and unfortunate turn that eliminated many fascinating stories, as well as the big ratings they would have most certainly garnered, and momentarily compromised the entire reason for Eliot Ness to do a weekly television series. With this limitation, however, the series would also be imbued with the challenge to often create their own colorful (if totally artificial) rogues gallery.

Thereafter, the FBI’s Los Angeles Crime Research Section monitored The Untouchables very closely “to determine if any future misrepresentations of bureau cases are perpetrated,” and detailed records were kept of each episode for its entire network run. But it wouldn’t be long before Bob Stack would unintentionally send the over-sensitive Bureau Chief into another foaming lather over a casual remark in TV Guide. Years later, when Quinn Martin produced the FBI series with Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., the bureau exercised complete control over the entire production, and Hoover, often given to fits over the most minor details, tried eight times in its nine year run to have the series canceled.

Ma Barker And Her Boys never aired on the network again, but her single telecast and 16mm syndicated prints distributed worldwide for nearly thirty years carried a voice-over during the credits:

“Desilu Productions wishes to point out that the FBI, although not being featured in tonight’s program, had the principle jurisdiction in the Barker Case and was responsible for the handling and eventual solution of it. “

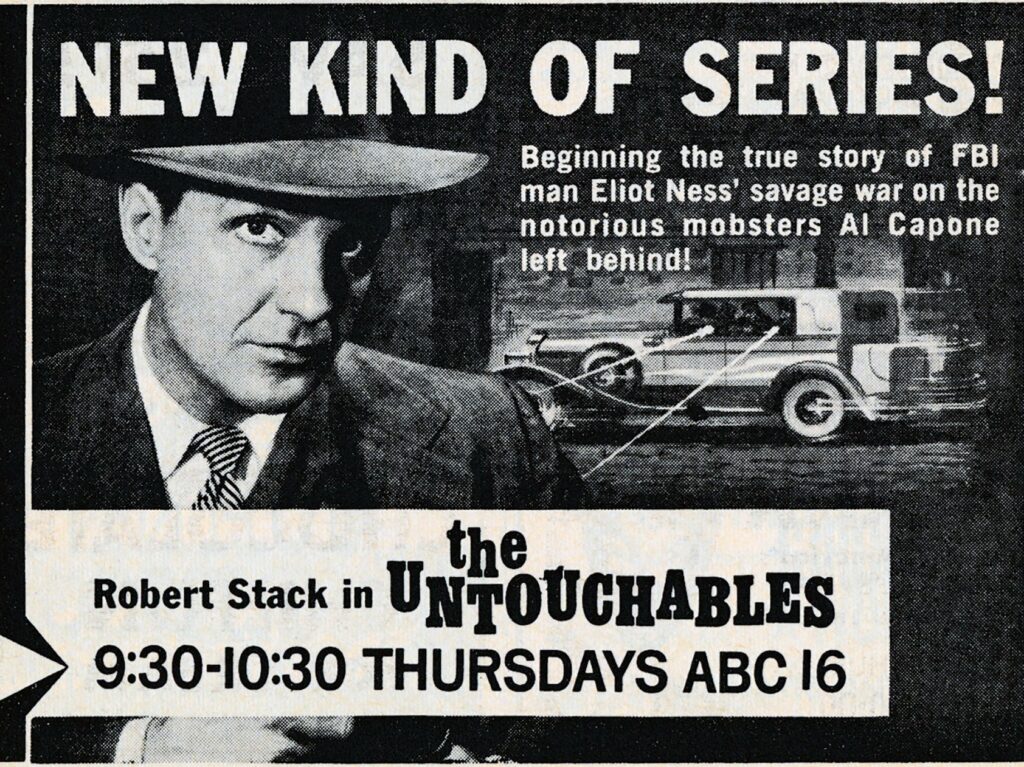

Arnaz’s apology, the disclaimer tacked onto the program’s credits and the promise to refrain from future crimes against the bureau prevented Hoover from making a federal case out of the affair. But the October 10 issue of TV Guide, in promoting the “new kind of series”, erroneously billed Eliot Ness as an FBI agent and worse, proclaimed the upcoming stories to be true.

A new kind of…fiction.

OBSERVATIONS

• Flashbacks are a useful framing device and stylistic choice, but this is the only episode to use them.

• A.D. Flowers would go on to win an Oscar for his special effects carnage in 1970’s Tora, Tora, Tora.

HISTORICAL NOTES

• Ma Barker was a popular villain for film and television, appearing by name or likeness in a handful of films as early as 1940, including the FBI Story (1959), Ma Barker’s Killer Brood (1960), an episode of Batman in 1966 and others.

• While her true leadership role within the gang has been disputed by historians, one of the most amusing descriptions of Ma Barker comes by way of a Harvey Bailey, a known criminal and associate of the gang, wherein he said Ma Barker “couldn’t plan breakfast…” let alone a criminal enterprise.

• Historians note that the real-life gun battle between the Barkers and the FBI resulted in over 1,500 rounds being exchanged. Sounds about right for an episode of The Untouchables.