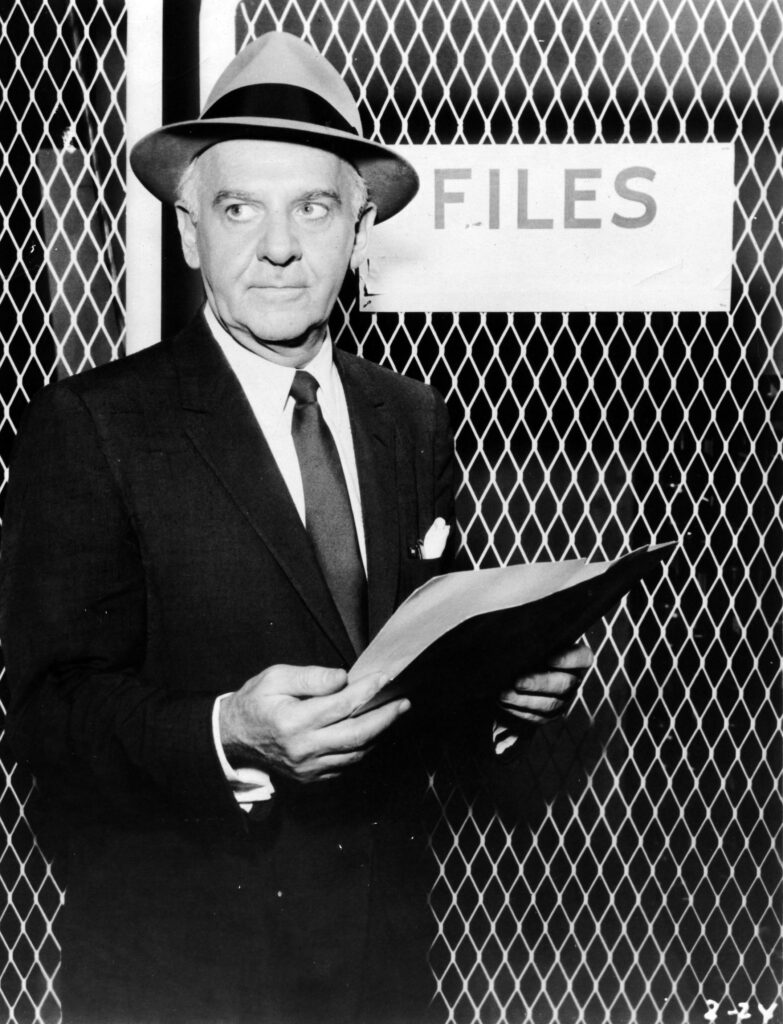

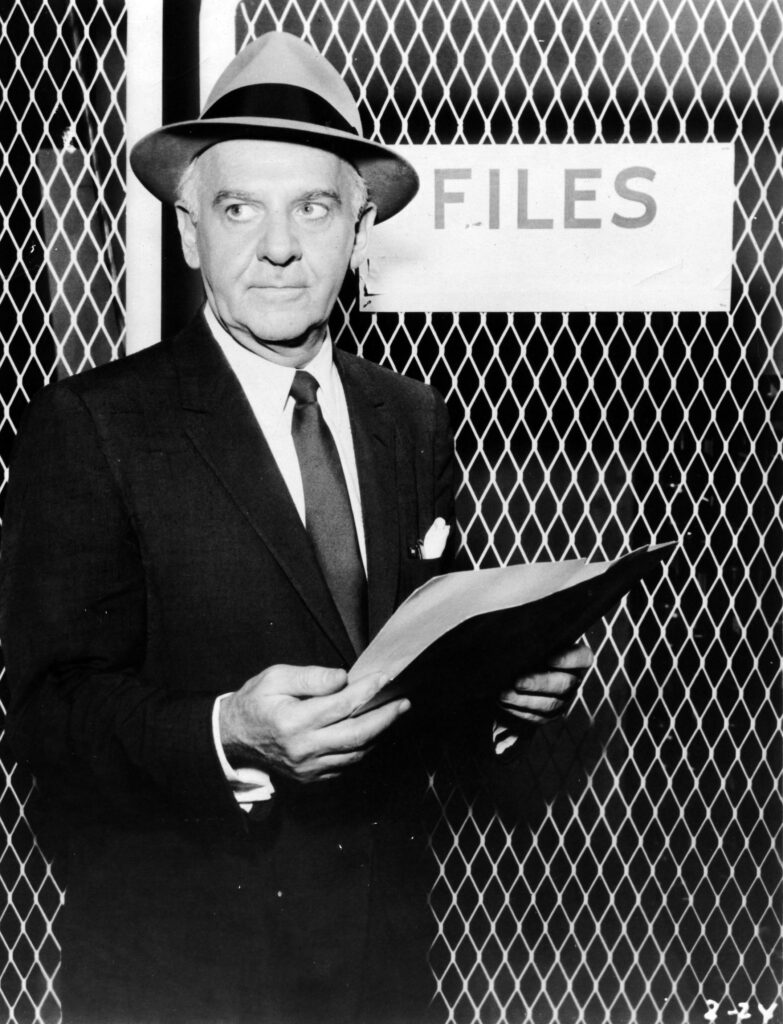

Walter Winchell (1897 – 1972)

Aptly portrayed by himself, Winchell was a real‑life journalist and radio commentator for four decades beginning in 1920. First a vaudeville performer then a writer for The Vaudeville News, he is widely regarded as the first to mix show business with journalism creating the newspaper gossip column in the New York Evening Graphic in 1924. An immediate success, he moved to the New York Daily Mirror in 1929, where his six daily columns, first about Broadway then entertainment in general, became a national feature. At the peak of his career, his newspaper audience was estimated at nearly fifty million readers.

Aptly portrayed by himself, Winchell was a real‑life journalist and radio commentator for four decades beginning in 1920. First a vaudeville performer then a writer for The Vaudeville News, he is widely regarded as the first to mix show business with journalism creating the newspaper gossip column in the New York Evening Graphic in 1924. An immediate success, he moved to the New York Daily Mirror in 1929, where his six daily columns, first about Broadway then entertainment in general, became a national feature. At the peak of his career, his newspaper audience was estimated at nearly fifty million readers.

In addition to his newspaper work, he went on radio in 1932, over the Mutual network where his clipped, nasal delivery sometimes bordering on a shout became famous worldwide with the often satirized opening line, “Good evening Mr. and Mrs. America and all the ships at sea… ”

He became extraordinarily influential by covering every subject from politics to crime, despite charges that his reporting was often seriously in error. Arrogant, abrasive, and feared throughout the entertainment world, Winchell is said to have had table 50 wired at New York’s famous Stork Club to eavesdrop on the exclusive night spot’s famous diners. Celebrities were equally amazed and annoyed at his ability to snoop into their most private affairs.

As the premier purveyor of hot scoops, steamy news, and general gossip, Winchell had little difficulty in maintaining a large radio and newspaper audience for many years. From that, he commanded and got the attention of a wide variety of famous personalities on both sides of the law. While he associated with hundreds of prominent figures, his lasting friendships were few and often convulsive.

The most celebrated of the handful of close friends was J. Edgar Hoover, whom he met during the Lindbergh case in 1934. Some years later, their close association began, with Hoover supplying Winchell with “inside information” and Winchell reciprocating by promoting the G‑Man image more than any other journalist. They consulted often, meeting frequently at “Winchell’s table” at the Stork Club and shared vacations in Florida. Hoover routinely provided Winchell with a limousine, driver, and bodyguards whenever the columnist received threats against his life, which occurred with some frequency.

The most well‑publicized effect of their friendship was the surrender of Murder, Inc., founder Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, at‑large for two years as one of the country’s most‑wanted fugitives. Arranged by Winchell in late August 1939, it was Hoover’s last personal arrest. Though ultimately successful, the affair nearly terminated their rapport.

The relationships Winchell maintained with stars’ press agents were often stormy. He is widely believed to have been the model for the venomous lead character in former press agent J.J. Hunsecker’s Sweet Smell Of Success (1957), starring Burt Lancaster as the Winchell‑like reporter and Tony Curtis.

Winchell is said to have reported that actress Betty Grable had been stricken with cancer at the height of her career. The star’s incredulous press agent immediately phoned a newspaper to protest and was told by the switchboard operator that “Winchell said she had cancer. She’d better have it if she knows what’s good for her.”

Before his 1952 television debut, he appeared in several unmemorable films, including Love and Hisses (1937). His first series for ABC television, The Walter Winchell Show, met with limited success, but his sponsors fled when he implied Adlai Stevenson was a homosexual.

Though his status as a newsman remained legendary, it wasn’t until he began ridiculing popular newcomers Marlon Brando, James Dean, and others, that the public began to view Winchell as a declining voice in entertainment. His next effort for ABC in 1957, The Walter Winchell File, lasted five months, but he would return to the limelight narrating Beau James, an expensive period film on the political career of New York mayor Jimmy Walker, released that same year starring Bob Hope and Vera Miles.

By the time Desi Arnaz began considering him as narrator for The Untouchables, the renowned columnist had both feet on the accelerator towards obscurity. Not only was he busy setting bridges aflame with lawsuits against ABC over the Winchell File failure, but his typically reckless 1953 story tying Lucille Ball to the Communist Party during the McCarthy Era had not been entirely dismissed by Arnaz’s wife.

Tom Moore, ABCs programming chief, wanted a new voice for the series, one that was pleasing to viewers, but despite the odds, Arnaz prevailed and the decision to use him remains a masterstroke. After all, Winchell was the voice of the 1930s. His authoritative, breathless, tobacco‑cured bark recalled the era with such authenticity, it transformed The Untouchables into cinema verite, fooling viewers into believing the series was historical fact despite Winchell’s long history of shamelessly inaccurate banter.

At length, Winchell had arrived to the ultimate forum, the perfect medium for his style of theatrical deception. It was to be his final achievement and most enduring legacy. After the series, Winchell dabbled at the only thing he knew best, but it went unnoticed. He retired in 1969.

If few remember Winchell fondly for his work, he did little to secure lasting friendships at Desilu. He appeared only briefly at Glen Glenn Sound to do the voice‑overs, sometimes two or three program’s worth at a sitting, then retreated. He worked straight from the script and never changed a word of copy prepared for him. His narratives were written by the show’s writers in a style he most likely would have delivered in his most lucid moments on radio. Winchell’s contribution was limited to the legacy of his name and those unique, inimitable vocal cords.

Screenwriter John Mantley recalls his single consultation with Winchell by phone as an unpleasant experience, not repeated. The subject of the call is lost to the years, but Mantley, certainly the most prolific writer for the series, was greeted with the same abrasive contempt Winchell seemed to hold for all mankind. “He was an arrogant, nasty man, but he read what I wrote for him,” says Mantley. “I never called him again.”

In Winchell’s case, talk was anything but cheap, but neither was it exorbitant. In the game Trivial Pursuit, a question asked, “Who narrated The Untouchables for $25,000 an episode?” The question is in error. $25,000 would have been one-quarter of the entire budget for a single episode in the program’s first year. The figure reflects his salary for an entire year.

After retirement in 1969 following his son’s suicide, Winchell became a recluse. Walter Winchell died on February 20th, 1972 – with only his daughter in attendance at the funeral.

A blue-eyed, imposingly good-looking leading man in theatrical films beginning in 1939, Stack once feared that any role in television, leading or otherwise, would be viewed as heralding the downside of his career, and he at first refused the role. Signing on to spite his agent, Stack would bring to the character of Eliot Ness a measure of reinforced concrete. He would be no ordinary peace officer with badge and gun, but rather the entire United States federal government, conveying to all concerned the illusion that confronting him was futile, possibly suicidal. Through Stack’s portrayal, Eliot Ness became an instant all-American hero virtually overnight and propelled an accomplished film star into the national limelight as no prior theatrical engagement had.

A blue-eyed, imposingly good-looking leading man in theatrical films beginning in 1939, Stack once feared that any role in television, leading or otherwise, would be viewed as heralding the downside of his career, and he at first refused the role. Signing on to spite his agent, Stack would bring to the character of Eliot Ness a measure of reinforced concrete. He would be no ordinary peace officer with badge and gun, but rather the entire United States federal government, conveying to all concerned the illusion that confronting him was futile, possibly suicidal. Through Stack’s portrayal, Eliot Ness became an instant all-American hero virtually overnight and propelled an accomplished film star into the national limelight as no prior theatrical engagement had. Aptly portrayed by himself, Winchell was a real‑life journalist and radio commentator for four decades beginning in 1920. First a vaudeville performer then a writer for The Vaudeville News, he is widely regarded as the first to mix show business with journalism creating the newspaper gossip column in the New York Evening Graphic in 1924. An immediate success, he moved to the New York Daily Mirror in 1929, where his six daily columns, first about Broadway then entertainment in general, became a national feature. At the peak of his career, his newspaper audience was estimated at nearly fifty million readers.

Aptly portrayed by himself, Winchell was a real‑life journalist and radio commentator for four decades beginning in 1920. First a vaudeville performer then a writer for The Vaudeville News, he is widely regarded as the first to mix show business with journalism creating the newspaper gossip column in the New York Evening Graphic in 1924. An immediate success, he moved to the New York Daily Mirror in 1929, where his six daily columns, first about Broadway then entertainment in general, became a national feature. At the peak of his career, his newspaper audience was estimated at nearly fifty million readers. No stranger to Robert Stack and his intrepid crew, Paul Picerni, who played Lee Hobson, was the newest of The Untouchables in the Second Season, and appeared in the two-part program which preceded the Emmy award-winning TV series. However, in the early show, Picerni played a cafe operator, and though the role gave him the opportunity to slap Barbara Nichols around, Stack and his men eventually gave him his lumps, so he was happy to be on the right side of the law.

No stranger to Robert Stack and his intrepid crew, Paul Picerni, who played Lee Hobson, was the newest of The Untouchables in the Second Season, and appeared in the two-part program which preceded the Emmy award-winning TV series. However, in the early show, Picerni played a cafe operator, and though the role gave him the opportunity to slap Barbara Nichols around, Stack and his men eventually gave him his lumps, so he was happy to be on the right side of the law. Nicholas Georgiade’s Enrico Rossi was Desilu’s “good-guy” Italian, and was discovered by Lucille Ball while he was playing a leading role in a local little theater production of View From The Bridge.

Nicholas Georgiade’s Enrico Rossi was Desilu’s “good-guy” Italian, and was discovered by Lucille Ball while he was playing a leading role in a local little theater production of View From The Bridge.  Rugged Abel Fernandez, a tough but sensitive ex-paratrooper who used to make a living with his fists, viewed his part in The Untouchables, as the biggest break of his new career as an actor. He portrayed William Youngfellow, Cherokee Indian member of Elliot Ness’ gangbusting group of Department of Justice agents. Youngfellow was based on William Gardner, a Native American Treasury agent who served as a part of the real-life squad.

Rugged Abel Fernandez, a tough but sensitive ex-paratrooper who used to make a living with his fists, viewed his part in The Untouchables, as the biggest break of his new career as an actor. He portrayed William Youngfellow, Cherokee Indian member of Elliot Ness’ gangbusting group of Department of Justice agents. Youngfellow was based on William Gardner, a Native American Treasury agent who served as a part of the real-life squad. Steve London appeared in 63 episodes of The Untouchables as Jack Rossman, who was loosely based on Paul Robsky, the wire-tap expert on Ness’ squad. London appeared in bit roles throughout his short career on film and television.

Steve London appeared in 63 episodes of The Untouchables as Jack Rossman, who was loosely based on Paul Robsky, the wire-tap expert on Ness’ squad. London appeared in bit roles throughout his short career on film and television. Known as The Enforcer, Frank Nitti became one of the all-time greatest recurring TV villains, eclipsing the notorious and often named but virtually never seen Capone. Portrayed memorably by Bruce Gordon in just 23 episodes as well as the Desilu Playhouse, Gordon brought to the Nitti character a single‑mindedly evil, unforgivingly treacherous yet somehow likable, even enjoyable persona unmatched by any other in television history apart from oil baron J. R. Ewing of the series Dallas.

Known as The Enforcer, Frank Nitti became one of the all-time greatest recurring TV villains, eclipsing the notorious and often named but virtually never seen Capone. Portrayed memorably by Bruce Gordon in just 23 episodes as well as the Desilu Playhouse, Gordon brought to the Nitti character a single‑mindedly evil, unforgivingly treacherous yet somehow likable, even enjoyable persona unmatched by any other in television history apart from oil baron J. R. Ewing of the series Dallas.