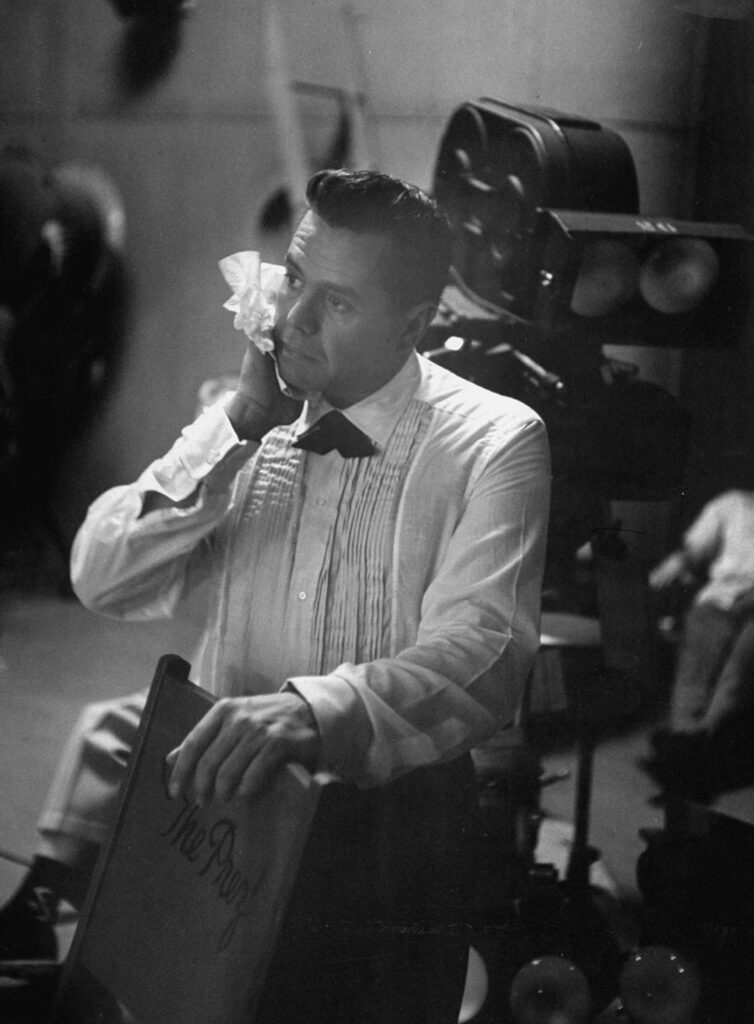

Only recently has Desi Arnaz come to be recognized as television’s principal architect. Obscured throughout his entire career by his flamboyant wife, Arnaz did quietly for television what Hal Roach had done for comedy, what Walt Disney had done for the animation. Lucille Ball got the laughs, the headlines, and the roses, but it was Desi Arnaz who ran the company store, hired the help and stumbled from one brilliant idea to the next.

With the acquisition of RKO Studios, Desilu was poised to become an upstart in the burgeoning television production industry.

One day in 1940, the couple bought a five-acre tract in once-rural Chatsworth in the rapidly developing San Fernando Valley outside Los Angeles. There they built a modest country Ranchito they named Desilu, a moniker novelist Thornton Wilder later noted sounded like “the past participle of a French verb.” Slightly more than a decade later, this name would headline a company founded to produce and film I Love Lucy, television’s most celebrated and successful situation comedy developed from Lucille Ball’s 1940s radio program, My Favorite Husband.

I Love Lucy was a series born to save a marriage and one CBS executives believed might sustain only marginal appeal. But the subsequent universal popularity of the wacky redhead and her English‑impaired, Cuban bandleader husband propelled its stars and their namesake production company into the forefront of the industry. Arnaz pioneered the live audience format and the use of multiple film cameras early on and continued to improvise in nearly every other aspect of the business for another decade.

By the late 1950s, Desilu Productions, occupying the former RKO sound stages in Hollywood and the sprawling Culver City backlots where David O. Selznick filmed Gone With The Wind, had swollen into the largest motion picture company in the world. Producing just for television, Desilu had surpassed film giants MGM, Warner Brothers, and Paramount Pictures. RKO, once a joint venture created by RCA and Keith‑Orpheum Theaters, was now firmly in the hands of two of its one-time contract artists. With real estate holdings, a record company, a publishing division and responsibility for providing production facilities for some 26 weekly programs, the Desilu signature for a time autographed nearly everything Americans watched and enjoyed from the little picture box.

On May 6, 1957, after 179 installments, I Love Lucy concluded its six‑year network run. The marriage of its stars, long troubled by the very institution created to save it, was in disarray and on the verge of collapse for the second time.

Eleven days later on May 17, an obscure printing company executive named Eliot Ness died. He was 54 years old. Until he died, Ness had been working with UPI correspondent Oscar Fraley on an autobiographical account of his career as a Treasury agent in Chicago during prohibition. He had been approving the final drafts when he went to the kitchen for a drink of water and crossed over into eternity from a heart attack. His legend was soon to follow.

Later that same year “The Untouchables” was published and picked up as an option by Warner Bros. producer Ray Stark. Warners still held the option when a summary of it fell across Desi Arnaz’s vacationing lap in July 1958, shortly before CBS launched the Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse. The hourlong anthology would offer, among other things, a place to continue on a monthly basis, the I Love Lucy format called The Lucy‑Desi Comedy Hour. If nothing else, the Comedy Hour would provide the heavy makeup required to cover a seriously troubled marriage. They were still America’s favorite couple, but hints of their explosive relationship were becoming the fodder of gossip spreaders.

THE DESILU PLAYHOUSE

Lois Green, a story editor for Desilu, was the first to believe Ness’s book would make an interesting and sensational idea for the Playhouse. She had stumbled upon it, found it difficult to set aside and practically copied the entire thing for dispatch to Arnaz’s vacation retreat, on the beach near the Del Mar race track just north of San Diego, where the producer was known to drop huge sums in pursuit of escape.

TV Guide’s Dwight Whitney probably summed up best what happened next in a story published in that magazine in August 1962: “Sometime after the sixth race…bells began to clang inside the Arnaz brain thereby setting off a chain reaction which is still rattling windows from Gower Gulch to Capitol Hill.”

It was December 1958, before Stark, unable to develop the property with a decent script, allowed the option on Ness’s book to lapse. Arnaz pounced. Once the rights to “‘The Untouchables” were obtained, he dropped the project into Playhouse executive producer Bert Granet’s disengaged mind. Granet, preoccupied with an impending and no doubt well-deserved vacation in Europe, quickly deposited the book into screenwriter Paul Monash’s mailbox with notes on what sort of treatment he thought the script should get. While all of this was going on, things had not been going well for the new Desilu Playhouse, and CBS was considering its alternatives. The Lucy‑Desi Comedy Hour was being well received, but the rest was looking like filler despite top talent before and behind the camera.

The Playhouse format was certainly not an original concept. The Kraft Television Theater was the first of the major sponsor anthologies in 1948, followed by dozens more like Playhouse 90, the Alcoa Hour and the 20th Century Fox Hour. In the two years the program aired, it is remembered for the handful of Lucy‑Desi Comedy Hour episodes that preempted its serious format and for giving life to two other programs that would live for decades after their network runs: Rod Serling’s remarkable Twilight Zone and a series with a name that had been, prior to 1959, associated only with third‑world lepers.

Desi’s production studio had little going for it in the late 1950s, but the recently acquired autobiography of Prohibition agent Eliot Ness held promise.

The Playhouse had little going for it and was failing to make a serious showing in the ratings. It needed a swift kick, preferably up, and Arnaz was ready for another challenge.

In December 1958, Desilu Productions had become a public corporation. Arnaz could still gamble as he did nearly a decade earlier with I Love Lucy when the money was his own “babaloo” bucks, but now he had a boardroom full of button‑down bean counters second-guessing his dice rolls. He was about to undertake the most ambitious and expensive event ever produced primarily for the small screen up to that time. It would be the first of the made‑for‑TV movies.

The first problem wasn’t money, a good script or who would play whom, but something far more personal. In one of those peculiar twists where lives cross then double back years later, Sonny Capone, physically resembling his notorious father, had been one of Arnaz’s closest friends while the two were classmates at St. Patricies High School in Miami Beach during the Arnaz family’s early years in Florida. They had been out of touch for years.

The subject of his father had politely never come up in his association with Sonny, even though Arnaz had visited the estate on numerous occasions during the period when Capone was confined at Alcatraz. Although Arnaz had never met The Man, later reclusive and suffering from the venereal disease that would eventually kill him, he did encounter him on the telephone one day when calling for Sonny some years after Capone’s release.

Sonny had already heard about Ness’s book and quietly hoped it would go away, but he was more concerned about an Eliot Ness‑less feature film called Al Capone starring Rod Steiger, then in post-production and scheduled for a summer release. The news that the family name would not only be all over the country on theater screens but television as well was not warmly received. The phone call, the first they’d had in years, turned into a classic train wreck – they collided head-on.

Arnaz explained that if he didn’t do it, someone else with less appreciation for the Capone family would. He was unable to convince Sonny that he would handle the affair with some discretion. The call ended abruptly when all cordiality was lost and Sonny threatened to sue. It was the last contact between the Capone family and Desi Arnaz until the lawsuit, but the relationship, indeed the friendship between Sonny Capone and Desi Arnaz, had been damaged irrevocably.

Arnaz made good his promise to handle Capone’s part with restraint. With his disarmingly persuasive charm, he made it clear that certain elements of Ness’s book should be left out of the Playhouse feature. Much of Capone’s legendary brutality would be glossed over, but it was likely to have been anyway. This was to be the story of The Untouchables, which hadn’t been told, rather than that of Al Capone, already widely known and about to be storied again on the big screen with a plainclothes Chicago detective as his main adversary.

Having been confined for a year in Philadelphia on a gun‑carrying charge, Al Capone would show up to deal with the “Ness problem” in the second of the two Desilu Playhouse installments, back in Chicago, furious and willing to knock heads, but without a baseball bat. So vicious was the legendary baseball bat tantrum, it would fail to find its way onto celluloid until 1987, in Brian De Palma’s feature version of The Untouchables, but even then, seriously scaled down. The story involves three hapless chaps, Joe Guinta, Albert Anselmi and John Scalisi, who conspired to overthrow Capone, then naively showed up at a banquet as Capone’s guests of honor only to have their brains become part of the proceedings if not mixed right in with the dessert cups. As if it could possibly have mattered, the battered trio was then shot up and later brought to rest just over the state line in an Indiana ditch.

Arnaz threw himself into the production as he had not done for any of the previous efforts. He had little choice. There was no doubt that it would have to be recut for release as a B‑grade theatrical feature and sold to foreign markets, not just to recover the loss, but to generate what is known as a good return on investment. Arnaz the actor, the artiste, could not have cared less, but he had to sell it to the accountants he had entrusted with the company purse. He presented his budget. $200,000 for each of the two hours, give or take. $400,000 thereabouts. By the time the prints were in the can, it would ring in just under a half million.

The studio wasn’t really prepared to handle a period theatrical feature of any consequence. Not only would Desilu’s Culver City lot need a complete makeover to flavor the look of suburban Chicago in the 1920s, but an entire brewery with working vats would have to be constructed on a sound stage at Desilu’s Gower Street studios. Hardly a stock item at the local prop house. Then there was the small matter of a fleet of period automobiles and vintage trucks in working or at least presentable condition. Add to this dozens of costumes, hundreds of assorted props and furnishings. It was no longer simply television with a couple of small sets and a handful of actors. The project took on Smithsonian proportions.

Arnaz wanted a script that would knock the couches out from under the sedate 1959 potatoes, lulled into a semi‑comatose state by endless uninspired fare. Not just more of the same cops and robbers to which everyone had grown accustomed, but untouchable cops and the sleaziest robbers ever to blacken the rugs of American living rooms.

When Monash surfaced with a sort of academic analysis of prohibition‑era thugs, written to conform to Bert Granet’s idea of the Capone case, Arnaz poured himself three fingers of bourbon, summoned the writer and placed an order for gangster drama supremo. If Monash failed, Arnaz was prepared to “…shoot right from the book.”

Quinn Martin, in his mid‑thirties and only recently moving up from sound editor to producer, got the call from Bert Granet. Martin wanted no part of it and the original script was the hurdle. Arnaz requested the pleasure of Martin’s company in the executive suite to talk it over. Utter charm, always one of his greater gifts, coupled with the notion of what a big success might do for Martin’s career, Arnaz convinced him that it might be worth the effort to take the chance. Charmed and persuaded, Martin went off to find the sequestered Monash and help him bail out the script. Director Phil Karlson joined them and the trio, now chased by a deadline, began to run in creative unison.

Karlson, known as the “toughest director in film noir,” had earned his particular tastes thanks to a hard-boiled upbringing in gangland Chicago. In a 1973 interview, he revealed that as a boy, he once helped protect a brewery from detection by police and in high school had witnessed a gangland assassination attempt connected to Dion O’Banion. It was obvious that Karlson was an ideal candidate to bring feature-film level grittiness to the Playhouse show.

Martin insisted that all night scenes be filmed after sunset rather than the transparently fraudulent filtered‑down method that never fooled anyone. This would later be called QM in the PM by union crews explaining their 4 a.m. arrivals home to annoyed and worried spouses. Cinematographer Charlie Straumer, getting wind of the night‑for‑night promise, planned for his own touch in the wet street look. Partly as a light‑bounce, but mostly for dramatic effect, this would require thousands of gallons of water that would often vaporize in the California climate between takes when shooting began.

Transportation chief Aaron Dom began turning over rocks to see what might roll out under its own power. Old car buffs were willing to loan vintage Buicks, Fords and Auburns, for a fee of course, but kindly no chase scenes or bullet holes. There would be more than a couple shiny roadsters parked on the street that were little more than empty shells with new paint. (Later, when the series began, Dom would learn that the cars had become stars in their own right and some care would have to be taken to ensure that a 1932 Ford did not chug through a scene while Winchell placed a story in 1930.)

Lynn Stalmaster, of Stalmaster‑Lister Casting, poured over mug files for actors with a certain law enforcement look and many unglamorous faces to flesh out a seedy Chicago underworld. (If anything can be said for The Untouchables, it might be that it found steady work for some of the most talented, but fiercely unfriendly faces on the West Coast.)

Director Karlson would also bring with him Neville Brand, one of the stars of his 1952 film Kansas City Confidential. Brand, looking nothing like the real Capone, would be tapped to play Scarface and in short order was dispatched to Italian Accent School.

Neville Brand sporting the Capone hat, cigar and signature scar, in a publicity photo for the Desilu Playhouse.

Paul Dubov, a bit player in Confidential, would be hired on as Untouchable Jack Rossman, setting a precedent that many character actors from 1940s and 50s would inevitably wind their way through the Desilu backlot once the show went to series. Virtually out of nowhere and without an audition, Karlson would also tap actress Patricia Crowley for the role of Ness’ wife, Betty Anderson.

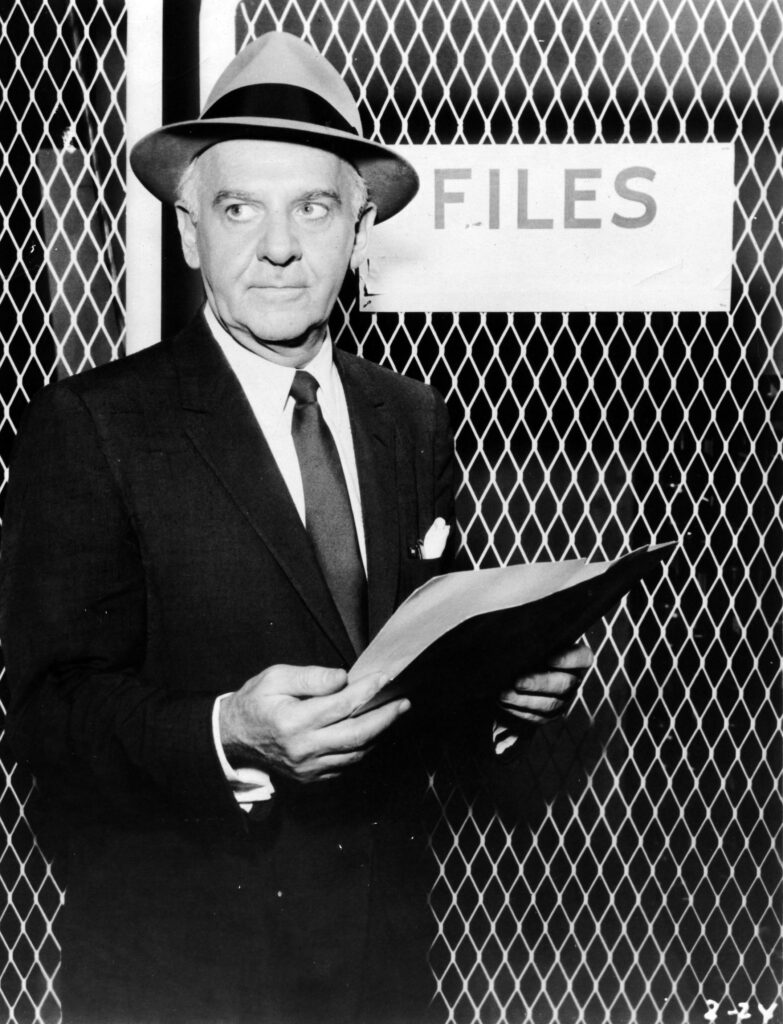

After decades of hard-hitting journalism and tabloid debauchery, Walter Winchell was licking his wounds from a number of late-career stumbles when he was hired to lend his tobacco cured inflection to The Untouchables.

Despite having one foot on the accelerator toward obscurity, Walter Winchell was brought on to give an authoratative air to the proceedings. Overlooking Winchell’s previous maligning of Lucy in the press by way of connecting her to the Communist Party and perhaps feeling indebted to Winchell over the failure of Desilu’s Walter Winchell File two years prior, Desi knew Winchell was the voice of the era and would lend authenicity to the era that would send Dragnet’s Joe Friday packing.

The genetic material for television’s first docu-drama were being gathered, but without a star attached for the lead role.

A TALE OF TWO VANS

It was now up to the Executive In Charge Of Production to catch the chief prohibition lawman, but Arnaz had been holding out for Van Heflin, who, it was rumored, had a large following in Europe, where the feature would recover American dollars.

When the Van Heflin idea invaded the stale air of the Monash cloister, the trio was furious. In no way did he fit their collectively evolving notion of Eliot Ness. Van Heflin was ready to sign, but the production delay caused by problems with the script sent him packing to a prior commitment. The creative team retired to their chambers relieved.

Seeming to work in alphabetical order, Arnaz then picked Van Johnson, but his manager (his wife) insisted that he be paid double the $10,000 fee since it was to be a two‑part feature. She knew that Arnaz was running up against the clock and the idea of simple extortion seemed like a good one at the time. Adios Van no. 2.

It was Friday. Capone was scheduled to take over Chicago first thing Monday morning. Production vice president Argyle Nelson, shepherding the beans, observed that if someone didn’t show up in Eliot Ness’s cheap suit in 48 hours or less, the studio stood to drop a great deal more than the extra $10,000 Van Johnson’s agent/spouse was demanding, with what 150 union people on call. The Pall Mall’s passed over the producer’s lips. There were colorful oaths in Spanish.

In desperation, he picked up the Academy equivalent of the Yellow Pages. Jack Lord leaped out at him. So did Fred MacMurray. Then Cliff Robertson. Then Bob Stack. Bob Stack…Deanna Durbin’s playboy. John Wayne’s co‑banana in The High And The Mighty.

Later that night, he found Stack at a restaurant with his wife, Rosemarie. Arnaz literally begged him over the phone to consider the role of Eliot Ness, a role that, he candidly advised he had already offered to two other actors who, for various reasons, would definitely not be considered further. Stack was amused, more so at being offered a job in the middle of the night than turning up third in the batting order. Arnaz pressed. Go home where the script would be waiting. Read it and call him back. It was 2 a.m. Saturday morning, Feb. 22, 1959.

At 6 a.m. Stack returned the call. The script was great (which is what all actors tell producers even if it’s the most worthless piece of rubbish ever to find it’s way off a typewriter ribbon‑‑and Stack wasn’t all that impressed), but who cares about prohibition and gangsters enough to make it work? (Besides, this was only television, right? Television with its tiny, still mostly black and white tube, crummy sound and silly commercials. Sure, he had done Playhouse 90, television’s only class act, and even Bob Hope’s often entertaining Chrysler Theater. But did he really want to get caught up with all that and miss out on any major offers that may surface unexpectedly?)

He gave Arnaz, by then leaving cigarette burns all over his transmitter, a gracious thanks, but no. There wasn’t time to really think it over on such short notice. No time for contracts or other legal formalities even though the business operated more like an auction with deals struck on the basis of nods, smiles and verbal handshakes. He would very much hate to agree now, only to back out tomorrow and leave a television producer yammering in a foreign language. Besides, he wasn’t the type to pull an Orson Welles. But Arnaz didn’t hear no. He unpacked the charm. He sweetened the deal.

And what a deal it was. $10,000 upfront – a handsome bit of change for a television part in 1959 – $7,500 an episode if it went to a series and 15% of the profits in Desilu stock. (A series? Stack recalled his first encounter with that nonsense year earlier with a flimsy, low budget, low brow swashbuckler pilot called The Phantom Pirate. It didn’t sell, thank God, and to make sure it would never see another sunrise, he had bought the property. No one would mention the idea again until after the reviews.)

Stack didn’t need the money. Financially independent and enjoying the charmed life of a tanned California tennis player‑skeet shooter, it mattered not if he ever made another film. Besides, he had just finished John Paul Jones, an expensive foreign location epic and was looking forward to some time off, some tennis and an occasional drive to the bank to check on the proceeds still washing ashore from that bit of work. Stack needed television a lot less than television needed Stack. It seemed like a huge goofy mistake getting talked into a job as a tin cop by a heavily medicated Cuban drummer in the middle of the night. No. Stack went to bed. Arnaz called Martin, Monash and Karlson.

After a fitful nap of sorts, Stack called his agent, Bill Shiffrin, who, of course, listened patiently to the Desi Arnaz proposal, Stack’s litany of doubts, then promptly fell in love with the whole project. What Stack calls a “violent argument” ensued. If anything, Stack would consider it just to show his agent what a dumb idea it truly was. He had no sooner hung up the phone than Desi’s creative team appeared, just in time for brunch. The only one with any history with Stack was Karlson, the “definitive director of melodrama,” as Martin would later refer to him in the trades. Later that evening, they left smiling.

By Saturday night, Stack was so willing to let the entire matter drop after a full day of wrangling that he was ready to agree to anything just to get nonfamily members out of the house and his ear away from a telephone receiver. He would have one more day to think it over, but he had already agreed to show up. Without a contract. As far as he was concerned, when he woke up Monday morning, it would be 1929. What the hell.

When Rosemarie dropped her husband off at Desilu Gower Makeup at 8 o’clock Monday morning, she had no way of knowing that their time together would amount to little more than stolen kisses between takes and candlelight dinners on drafty sound stages for the next four years. And they had been married for only three. Their daughter, Elizabeth, had just turned two.

When Rosemarie dropped her husband off at Desilu Gower Makeup at 8 o’clock Monday morning, she had no way of knowing that their time together would amount to little more than stolen kisses between takes and candlelight dinners on drafty sound stages for the next four years. And they had been married for only three. Their daughter, Elizabeth, had just turned two.

A gentlemen from wardrobe arrived and offered Stack a suit tailored to Van Johnson’s measurements. While new doubts about his latest career move continued to rise, Arnaz appeared, concealing a hangover and building another, beaming the Latin smile that had warmed television audiences throughout the first Cold War decade. Stack had shown up on the basis of a handshake for a part he ostensibly didn’t like, the third choice by a producer with whom he had no history. It was the moment of conception for a deep personal friendship they would share for the rest of their lives. The cameras, five of them, were being threaded with magazines of Kodak negative stock.

Though Ness never picks up the Thompson submachine gun in the Playhouse film, here Robert Stack strikes what will become an iconic pose with Keenan Wynn in a promotional still.

The creative team, Martin, Monash, and Karlson, continued last-minute rewrites and would go right on doing so throughout the entire production. Stack arrived on the set to find someone he knew well already there. Signed to play Joe Fuselli, the Untouchables’ driver with a prison record and a smile hinting at further larceny, was Keenan Wynn. Crazy, nutty Keenan Wynn, the friendly madman son of Ed Wynn, worked on Stack throughout the morning to dispel the demons and impart his own infectious approach to life in the motorcycle lane. Stack hopped on.

As day one wore on, Stack grew at ease and found his character in the initial readings and rehearsals. He already knew how to handle a gun, even those with real bullets, but had little time to consider how he might portray a man who, by then, should have been famous in his own right without any help from television. At length, he would settle on simplicity. He would underplay the character with a strange often silent, piercing presence. A man of few words, totally in control of himself Just beneath the surface, near periscope depth, would swim a composite of the three bravest men Stack had ever known.

Sometime that afternoon, Eliot Ness was born.

By nightfall, the Big Brewery Raid was ready for film. Even though the sequence wouldn’t show up until the second of the two parts it was easily the most expensive and best be done early rather than later, when money would grow scarce and comers get cut.

The most important scene, crashing through the doors then into a beer vat with a fiercely armored antique Coca‑Cola delivery truck, could be done one time only. Replaced by a stunt driver and a cameraman with a Mitchell 35mm handheld affair, Stack and Wynn stepped aside as the truck burst into the brewery with such force that one of the heavy doors flew off and landed in front of another camera position inside sending its operator into adrenal overload. Traveling the length of the set, it rammed a vat loaded with thousands of gallons of soapy water, sending television beer into a lather in every direction. The steel bands holding the vat together ripped violently apart and wrapped around the open cab striking the cameraman, breaking two of his ribs.

Ain’t we got fun?

Day one of principal photography with the brewery raid, replete with Coca-Cola truck in thinly applied stage paint doubling as Ness’ chariot.